When asked to picture an area of high biodiversity, you might imagine a rich, tropical rainforest or a vibrant coral reef. Maybe even an African savannah but certainly not a desert, with its reputation for being desolate and devoid of wildlife. Deserts are generally defined as areas of land that experience less than 250 mm of rain annually and as terrestrial ecosystems go; they are some of least well studied and most poorly understood, perhaps only beaten by Antarctica (which is itself a desert really).

The stereotypical view of deserts is that they unimportant for biodiversity and this can be seen in the breakdown of scientific ecology papers published between 2000 and 2011 – of these 67% focused on the forest biome whereas only 9% studied deserts (1). The lack of concern for deserts is also reflected in the amount of money dedicated to conservation programmes in deserts. Between 1992 and 2008, only 1% of the funding provided by the Darwin Initiative went towards desert conservation, with forests once again pinching the largest share of the pie (23%) (1). However, this neglect of deserts by both the scientific and conservation communities is not justified. Whilst the actual density of species found within deserts is lower than those of tropical forests; deserts cover 17% of the Earth’s land mass and simply due to their vast size, end up harbouring similar levels of biodiversity (2). For example, around 25 % of the world’s terrestrial vertebrates can be found in deserts (2) and no desert has more species in it than the Sahara.

The Saharan Problem

The Sahara is the largest (warm) desert in the world, covering around 43% of the African continent and has historically been home to 14 large vertebrate species, of whom 10 are endemic to the desert or the Sahel, the semi-arid region surrounding the core desert (3). Of these 14 species, all but one, the Nubian Ibex (Capra nubiana), have experienced significant decreases (greater than 65%) in range size compared to their historical distributions. In fact, 9 species have lost over 90% of their historic range and two species, the scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah) and the bubal hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus buselaphus), are now extinct in the wild (Fig. 1). Formerly large populations of lions (Panthera leo) and African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) have been wiped out around the southern edge of the desert and 12 of these large vertebrate species are now classified as threatened with extinction under the IUCN criteria (3).

Maps of range loss for 6 species in the Sahara (grey area). Showing current range (black shading) and range prior to 1800 (black line)

Causes of declines

Perhaps unsurprisingly these dramatic declines are thought to be due to human impacts. Despite the limited amount of development within the Sahara-Sahel, people are still found throughout and they compete with the animals for the limited resources available. Oases of fresh water are biodiversity hotspots within the Sahara, supporting a wide variety of endemic species such as the Sahara Bluetail (Ischnura saharensis) and are vital for the survival of larger mammals (4). However, people also rely on these lagoons for water and clashes with wildlife have already lead to the extinction of crocodiles within the Sahara (4). Extraction rates of natural resources, particularly fossil fuels have grown rapidly in the past decade, which directly threatens species though habitat fragmentation and degradation (4).

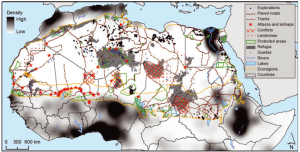

On top of this, human conflicts are increasingly a problem in the Sahel (Fig. 2). These have been suggested to cause the decline of numerous antelope species by allowing for elevated levels of poaching and by forcing more people to hunt for bushmeat in order to survive (4). Finally, while climate change poses an omnipresent threat to biodiversity across the globe, in the Sahara and other deserts, where temperatures are predicted to rise faster than anywhere else (3), climate change is a ticking bomb of biodiversity loss. It’s not really an issue yet but it will be soon.

Human activities in the Sahara-Sahel. Showing human population density in North Africa (black-white); areas of insecurity including regions with landmines, regions of long-standing conflict and attacks on people, infrastructure and kidnapping since 2003; occurrence areas of exploration of fossil fuels; major roads and tracks; protected areas and hypothesised biodiversity hotspots (refugia) in the Sahara-Sahel region. Adapted from (4).

Saving the Sahara?

Managing the Sahara-Sahel ecosystem to save biodiversity may actually be quite cost-effective when compared to other ecosystems, thanks to the low human densities and limited extent of cultivated land (3). With this in mind, the lack of protected areas within the Sahara needs to be addressed. Only 7.6% of its area is classed as protected (Fig. 2), significantly below the 10% recommended by the Convention on Biological Diversity (4). Positive steps are being made, such as the establishment of a 97, 000 km2 reserve in Niger, which covers around 150 of the 200 remaining wild addax (Addax nasomaculatus) (4) but more need to follow suit. Captive breeding and reintroduction programmes may be of help for some animals, such as the scimitar-horned oryx but these are expensive (a planned reintroduction of 100 oryx to Chad in 2015 is estimated to cost US$10 million) and not feasible for all species.

At the moment, the main problem is that we simply don’t know enough about what is actually happening to the Saharan ecosystem to effectively conserve its biodiversity. There is an urgent need to address this lack of knowledge with more research, identifying the precise threats to and trends of biodiversity. Any future conservation plans need to have a firm grounding in science and be tailored to local conditions to maximise their efficacy (3, 4).

The worldwide plight of desert ecosystems and their wildlife is finally gaining wider recognition but it is still not enough. We now are approaching the halfway point of the UN’s “Decade for Deserts and the fight against desertification” and of the UN’s “Decade on Biodiversity”. Maybe it is time for both to be considered together.

References

- S. M. Durant et al., Forgotten Biodiversity in Desert Ecosystems. Science 336, 1379-1380 (2012).

- G. M. Mace, H. Masundire, J. E. M. Baillie, in Ecosystems and human well-being, B. Scholes, R. Hassan, Eds. (Island Press, Washington, DC, 2005), vol. 5, pp. 77-122.

- S. M. Durant et al., Fiddling in biodiversity hotspots while deserts burn? Collapse of the Sahara’s megafauna. Diversity and Distributions 20, 114-122 (2014).

- J. C. Brito et al., Unravelling biodiversity, evolution and threats to conservation in the Sahara-Sahel. Biological Reviews 89, 215-231 (2014).

Pingback: Growing a World Wonder – Great Green Wall – Olive Network·