Picture this: it’s Monday morning. You wake up, open the curtains and… wait… what’s that? A chimpanzee in your vegetable patch?

I expect you’d pinch yourself; after all, you live in Canterbury. But for people in central and western Africa, this is no dream (Fig.1). If anything, it’s a living nightmare; one which could leave us without any chimpanzees at all.

Humans are part of the ape family, Hominidae. In this family, our closest cousins are the African great apes: gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos. Unlike humans, populations of these species are dwindling, and all are now classified as critically endangered.

Unsurprisingly, one of the biggest threats to African great ape survival is habitat loss. As human populations grow and our demand for resources rockets, tropical forests are being rapidly cleared for agriculture and urban development.

In an alarming revelation, a recent study found that only 10.7% of African great apes occur within protected areas (2). This means 89.3% of populations are vulnerable to the kinds of land use change listed above. As a result, these species are being driven from their natural environments and into human landscapes. The question is: how are they coping?

In some ways… quite well

Great apes are known for their behavioural flexibility: the ability to modify behaviour in response to changes in the local environment. Given how many populations have been thrusted into human landscapes, this adaptability has come in handy.

Let’s focus on crop feeding. Historically, deforestation in Africa has been driven by subsistence agriculture. This is where rural populations cut down trees, clear brush and grow crops to feed their families and livestock. These practices fragment great ape habitat and reduce the abundance of natural foods. In response, great apes have modified their feeding behaviour to suit this new agricultural matrix. All species consume human cultivars, with chimpanzees being the most well-studied culprit (Fig. 2).

So, what’s the problem?

Whilst losing some garden tomatoes to a chimpanzee might make an exciting story for me or you, it can be devastating for farmers who rely on crops for income and subsistence. A 2018 study found that 87% of farmers across Sierra Leone perceived chimpanzees as dangerous, with the main reason being crop feeding (3). Such perceptions often translate into the persecution and retaliatory killing of great apes.

Although groups respond flexibly to this risk (see this study for how chimpanzees night forage to avoid detection), these behaviours aren’t fool proof. Indeed, death due to agricultural conflict is reported across great ape ranges. Claw-like ‘mantraps’ used to protect cropland in Uganda have been implicated in the injury and death of chimpanzees for over a decade (4).

Unfortunately, for declining populations in fragmented habitats, the loss of even a few individuals can increase the likelihood of local extinction.

Why not just plant more natural food?

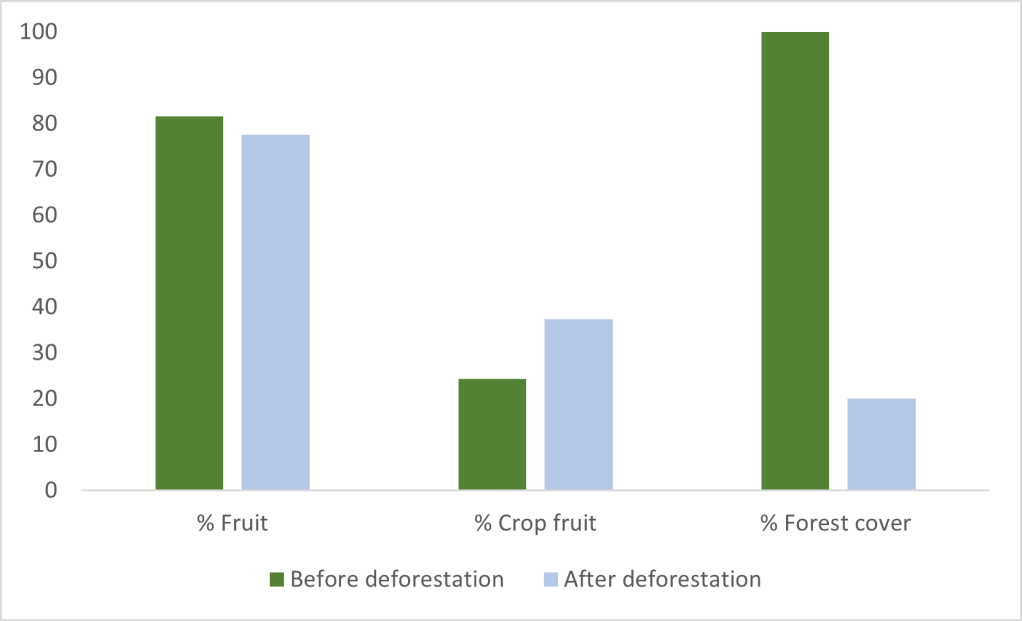

This is known as enrichment planting and, at first, it appears to be an easy fix. A 2020 study found chimpanzees to increase consumption of human crops after a period of deforestation, suggesting that crop feeding was driven by a reduction in natural foods (Fig. 3; 1). In this case, enrichment planting would be effective.

However, looking closer at this study reveals that deforestation was caused by agricultural expansion. So, did crop consumption increase due to wild food decimation or simply because more crops were available?

Whilst the answer probably lies somewhere between these possibilities, the wider base of research largely supports the latter. In Gorillas, for example, time spent eating human cultivars is determined almost completely by accessibility to agricultural fields; wild food availability has no significant effect (5).

In sum, crop feeding is rarely driven by necessity, but rather preference: crops are energy rich, easy to digest and clumped together for efficient foraging. Therefore, enrichment planting is often futile.

So, what’s the solution?

Given the findings above, conservation solutions regularly focus on reducing great apes’ accessibility to crops.

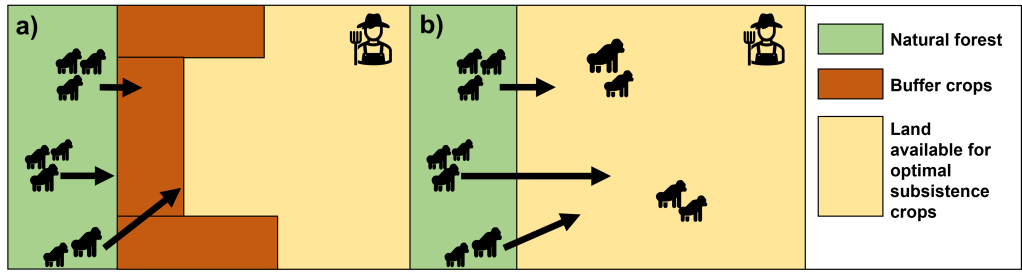

One popular method is cultivating ‘buffer crops’. This is where farmers plant foods that are unappealing to great apes around the edges of their land. Groups are less likely to travel through unpalatable fields to get to tasty crops, limiting crop feeding and mitigating conflict.

But here’s the problem: land holdings in Africa are typically quite small. As such, giving up land for cultivars that won’t make as much money or feed families as productively can increase socioeconomic pressures on local people, potentially aggravating conflict (Fig.4).

Alternative techniques include fences or non-lethal crop deterrents. For example, hand-held firecrackers can increase the perceived risk of crop feeding and keep unwanted foragers away. Unfortunately, these methods require time, money, and manpower that not all farmers possess.

What does the future look like?

Crop conflict between humans and African great apes is a complex conservation issue. With more and more populations living in unprotected landscapes, and agricultural expansion driving the decimation of wild forests, this pressure will only intensify.

But however much we want to see these species survive into the next century, we cannot sacrifice the livelihoods of local people to make this so. Blaming local populations for biodiversity decline without understanding what drives their behaviour is a historical mistake in conservation planning.

Creating conservation plans that work with farmers, rather than against them, will create sustainable futures for the great ape family in its entirety. Those solutions are unlikely to be perfect, but technologies like non-lethal crop deterrents are a start.

References

- M. R. McLennan, G. A. Lorenti, T. Sabiiti, M. Bardi, Forest fragments become farmland: dietary response of wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) to fast- changing anthropogenic landscapes. Am. J. Primatol. 82, e23090 (2020)

- Isabel Ordaz-Nemeth et al., Range-wide indicators of African great ape density distribution. Am. J. Primatol. 83, e23338 (2021).

- R. M. Garriga, I. Marco, E. Casa-Diaz, B. Amarasekaran, T. Humble, Perceptions of challenges to subsistence agriculture, and crop foraging by wildlife and chimpanzees Pan troglodytes verus in unprotected areas in Sierra Leone. Oryx 52, 761-774 (2018).

- M. Cibot, S. L. Roux, J. Rohen, M. R. McLennan, Death of a trapped chimpanzee: survival and conservation of great apes in unprotected agricultural areas of Uganda. African Primates13, 47-56 (2019)

- N. Seiler, M. M. Robbins, Factors influencing ranging on community land and crop raiding by mountain gorillas. Animal Conservation 19, 179-188 (2015).