With the dramatic rate of global biodiversity loss, the need to protect our planet has never been more urgent, but how can this be done? A new target has been put forward with one goal in mind: increasing our conservation efforts and restoring natural biodiversity destroyed through human pressures such as land exploitation.

Protected Areas: regions of land with an increased level of protection to wildlife and habitats, through banning or managing harmful activities

Designating Protected Areas (PAs) should help to prevent and then counteract biodiversity loss. Preserving biodiversity has never been more urgent. Loss of biodiversity can damage and potentially destroy ecosystems, the underpinnings of all wildlife. PA sites are designated regions for the most vulnerable species and/or biggest rates of biodiversity loss1. However, there is controversy surrounding these PAs, such as designation without implementation and geographical location2,3. The goal is to protect 30% of terrestrial land by 2030, but is this achievable and is this enough?

The target – 30×30: what does this mean?

There is a global target to protect 30% of terrestrial and inland territories by 2030 (30×30), ensuring significant conservation efforts are made to restore biodiversity through protecting damaged and threatened wildlife populations2,4. However, as pressure builds on our governments to produce results, is there possibility this goal is unattainable?

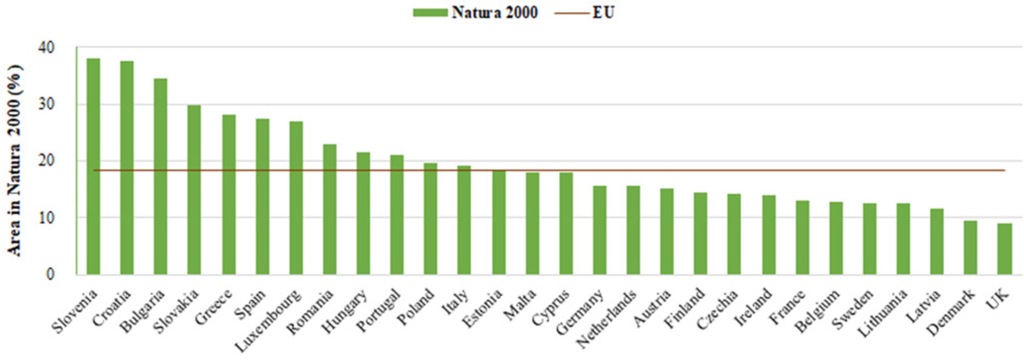

European governments have seen the urgency facing our planet and have committed to helping this global cry for increasing support into conservation. Currently, more than 18% of European terrestrial and inland areas fall under a protected area2,3,5.

The Green Deal and Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 are two important commitments made by the EU to prioritise biodiversity in Europe2. Yet there is more to these initiatives than there may initially seem; biodiversity is delicate, making it difficult to protect and restore. Issues arise when considering the connectivity between PA sites and the impact climate change will have on conservation efforts1,2.

Introducing Natura 2000

The EU orchestrates the biggest network of PAs globally, coordinating them to increase the conservation benefits afforded to wildlife and habitats within these areas5, called Natura 2000. This, in principle, creates safety for threatened and vulnerable species, whilst also holding all EU members to account – creating a strict guideline to employ sustainable and wildlife-friendly measures.

So, what are the main issues?

Whilst the designation total is, on the surface, quite an achievement, there are numerous issues facing European PAs. Lack of coordination between European countries and lack of effective connectivity between PA sites brings about doubt over their effectiveness2. This reduces conservation impact; whilst protecting specific areas is vital, species needing protection tend to migrate outside the PAs and therefore outside of protection.

There is unequal distribution to designation percentage size – certain countries are nowhere near the target (E.g. Sweden and Denmark) whereas some have already succeeded it (E.g. Croatia and Bulgaria)2,3. Conservation in countries with lower PA coverage will be less effective, so species loss and habitat degradation will still occur. This also creates issues protecting species endemic to countries with lower levels of protection, as they are still left vulnerable.

European PAs can lack adequate management plans, creating opportunities for poor enforcement of regulations and bans2,3. Urban sprawl into PA sites generally decreases their efficacy to protect biodiversity, as high levels of urbanisation lead to a low conservation value in these regions3. This is, of course, a difficult issue to counteract, due to the ever-increasing human population and the constant requirement for houses. Initiatives such as regenerative architecture are trying to tackle this.

Conservation will only be most effective when the impact of climate change is also taken into consideration1. As climate change influences how well an area can be conserved, synchronising and prioritising European PA sites with areas of high climate change activity is vital to help conserve biodiversity.

Is there hope the 30×30 goal will be reached?

These commitments made by the EU are a huge opportunity to hold each country accountable for their own biodiversity conservation efforts, against a pre-established set of guidelines and outcomes2,5. This could have a pivotal impact on biodiversity loss, potentially reversing some of the anthropogenic pressures being put on wildlife.

Increasing connectivity of the European PAs could play a critical role in ensuring the best conservation outcomes are met2. Implementing better management techniques can also increase the success of PAs2, which must be coordinated throughout Europe with regulations on the harmful activities strictly enforced3. Also, adjusting designation sites to synchronise with sites that are likely to feel the largest impact from climate change, can potentially increase the likelihood of a positive conservation effort1. It is only through marrying all these factors that PAs will have the most success, and this conservation target can be met – and more importantly, effective.

Balance must be struck, finding an achievable conservation goal which will start to reverse the negative impact humans have had on this planet. The 30×30 initiative is a great way to set a – what should be – achievable goal. Research-led designation criteria determining the key areas for protection can create a series of complex interlinking networks of protected areas. This network will potentially provide the most effective conservation outcomes, increasing biodiversity and helping re-establish threatened and vulnerable species.

Achieving this 30% target is vital for restoring hope for biodiversity!

References

(1) Lai, Q., Hoffmann, S., Jaeschke A. and Beierkuhnlein, C. (2022) Emerging spatial prioritization for biodiversity conservation indicated by climate change velocity. Ecological Indicators 138: 108829 doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.108829

(2) V. Hermoso, S.B. Carvalho, S. Giakoumie, D. Goldsborough, S. Katsanevakis, S. Leontiou, V. Markantonatou, B.Rumes, I.N.Vogiatzakis and K.L.Yates (2022) The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Opportunities and challenges on the path towards biodiversity recovery. Environmental Science & Policy 127: 263-271 doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2021.10.028

(3) Concepción, E.D. (2020) Urban sprawl into Natura 2000 network over Europe. Conservation Biology 35(4): 1063-1072 doi: 10.1111/cobi.13687

(4) Protected Planet (2022) Protected Areas (WDPA) (online) available at: https://www.protectedplanet.net/en/thematic-areas/wdpa?tab=WDPA [last accessed 13/11/2022]

(5) European Commission (2022) Natura 2000 – Nature and Biodiversity (online) available at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/index_en.htm [last accessed 13/11/2022]